I managed to get Letters to Jill from the library right before everything closed down at the end of March. I had been looking into the photocopier for the most part of 2020, particularly the Xerox 914 copy machine—Xerox's first photocopier to use ordinary office paper—but only landed on the work of Pati Hill recently after Steiner told me about her over a desk crit. Through my research I learned of the relationship between women and copy machines, a product of a long history of women being confined to mundane office tasks like photocopying.

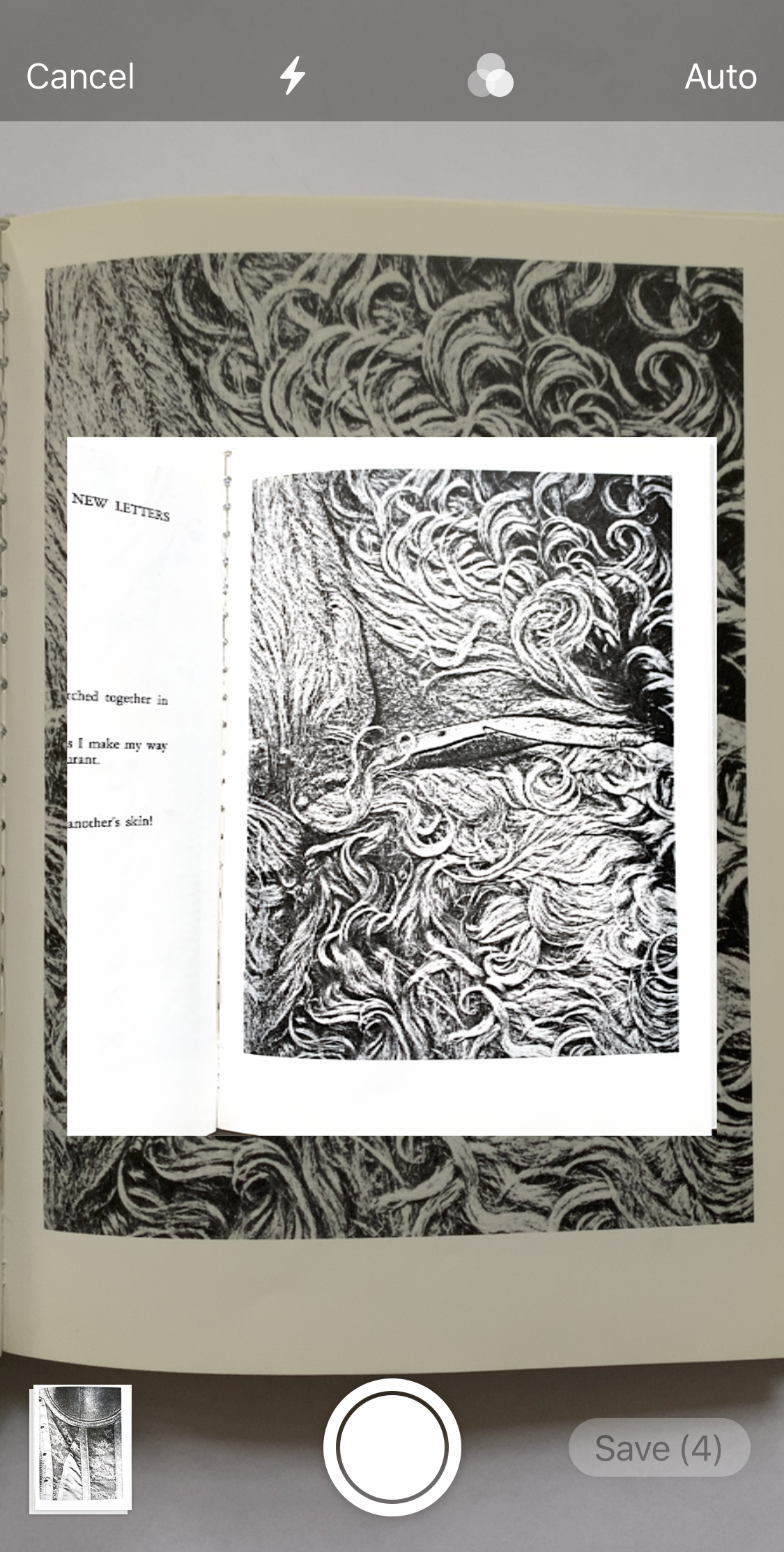

Hill worked as a model when she was young and I don't think she was ever an office secretary. She was a writer and photocopy artist best known for her copies of everyday objects made with an IBM copier in the early 1980s. Letters to Jill works as a compilation of notes on working with the photocopier. The title references the correspondence Hill had with Jill Kornblee of Kornblee Gallery, one of the first American galleries to recognize copy art as art and exhibit it. "Copies" meant office documents in the 1960s so there was a lot of resistance in looking at the medium as something other than that. Hill managed to convince Jill and it worked out. Photocopying was more than just documentation.

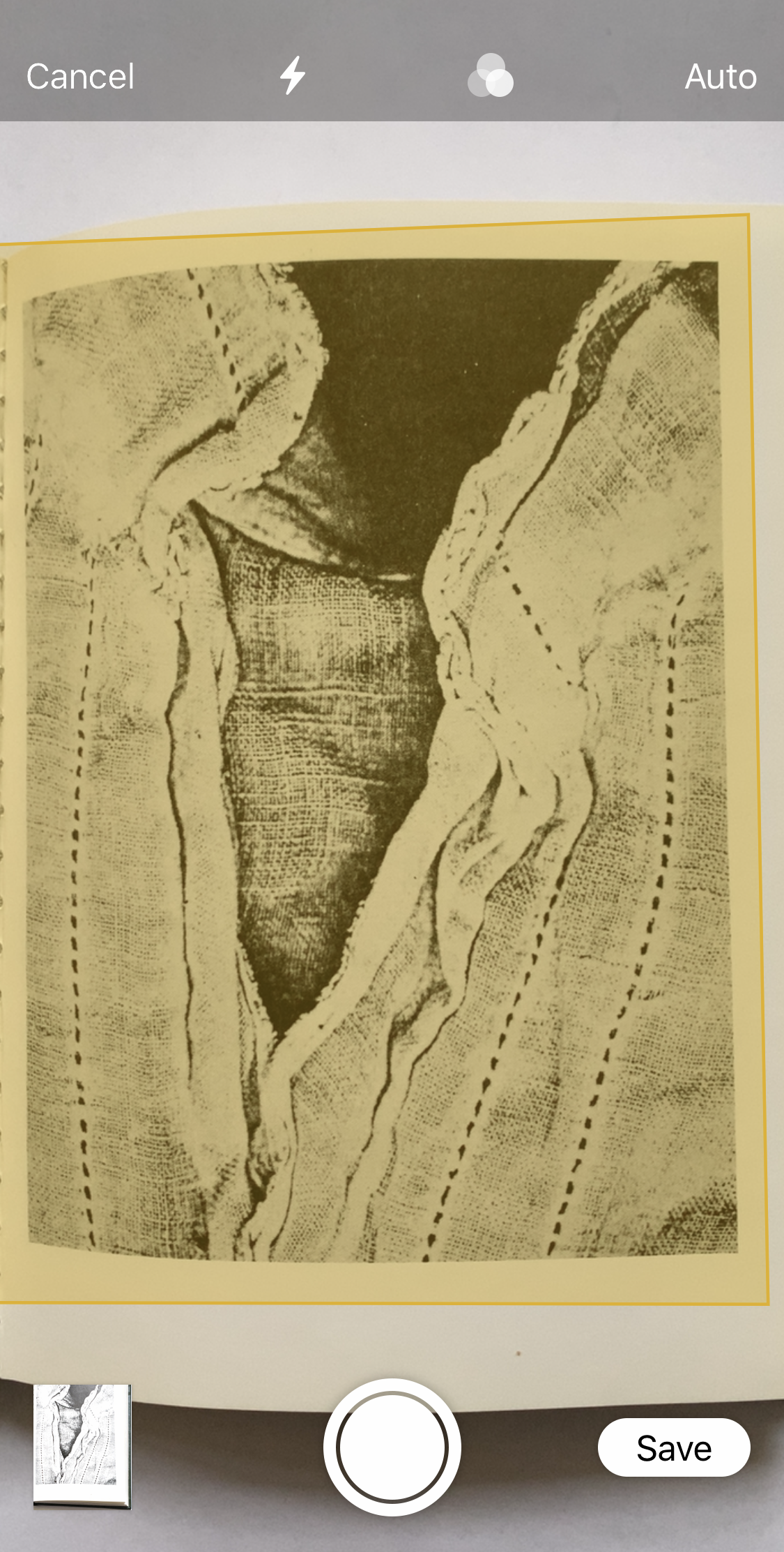

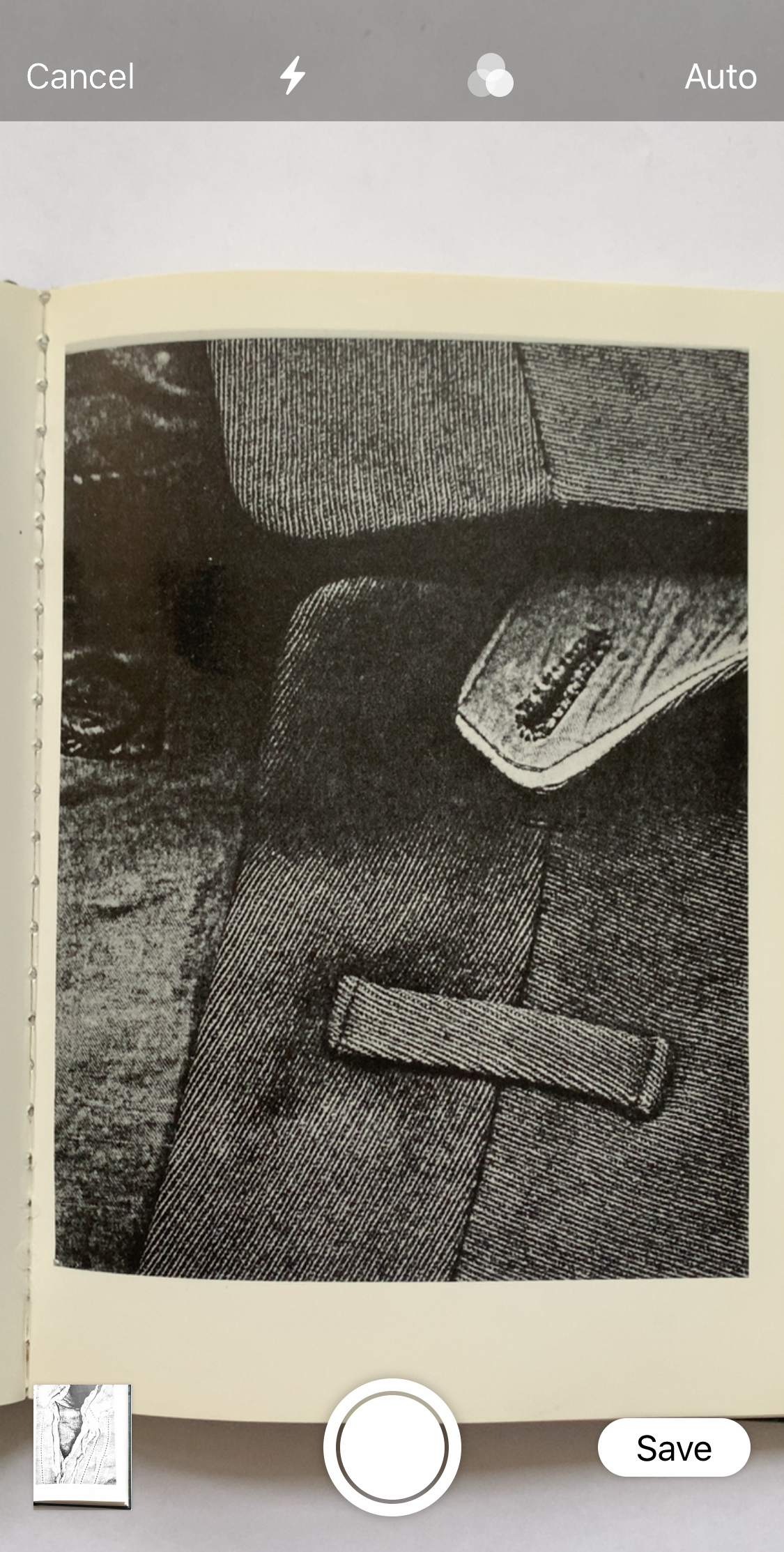

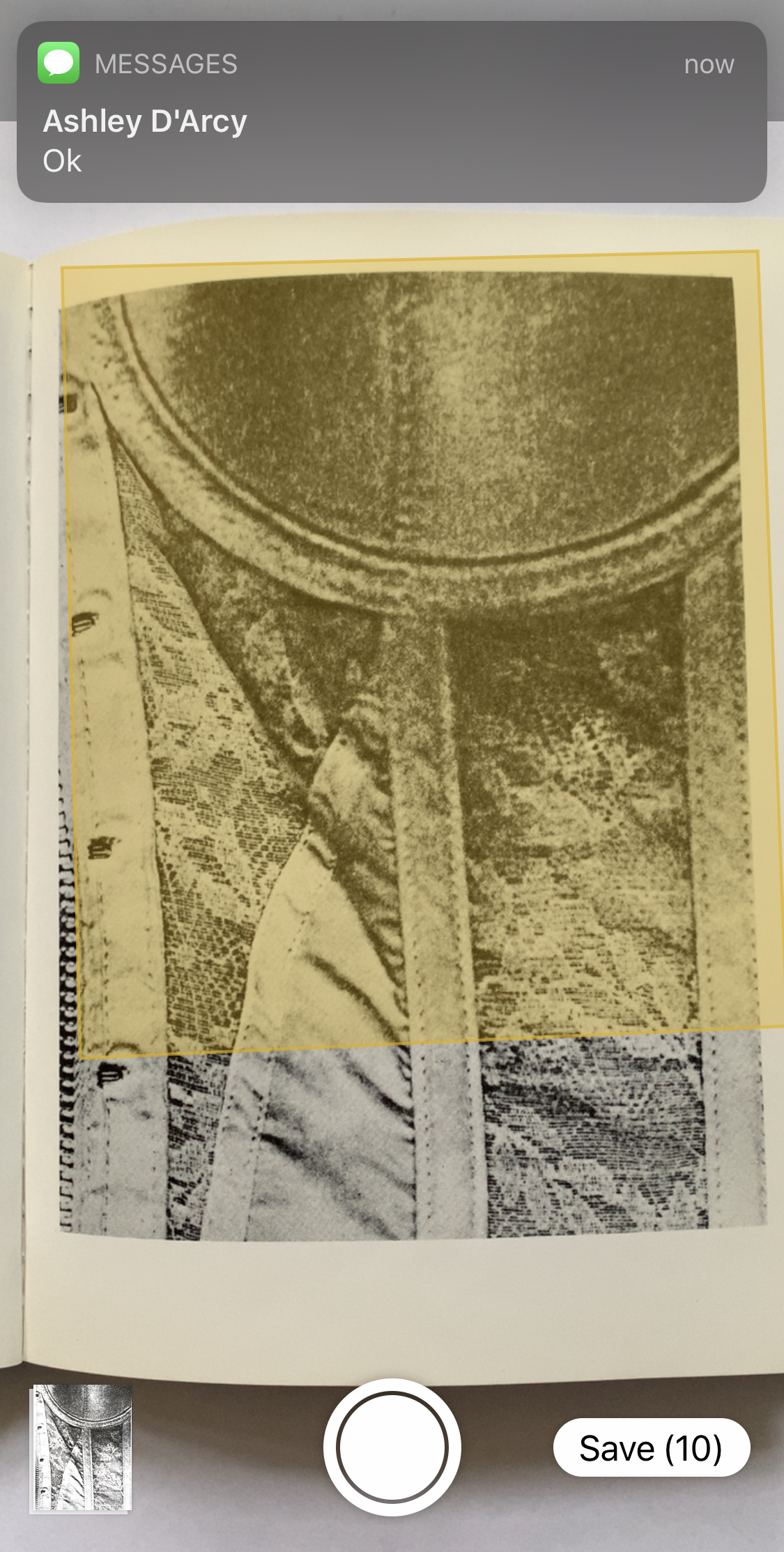

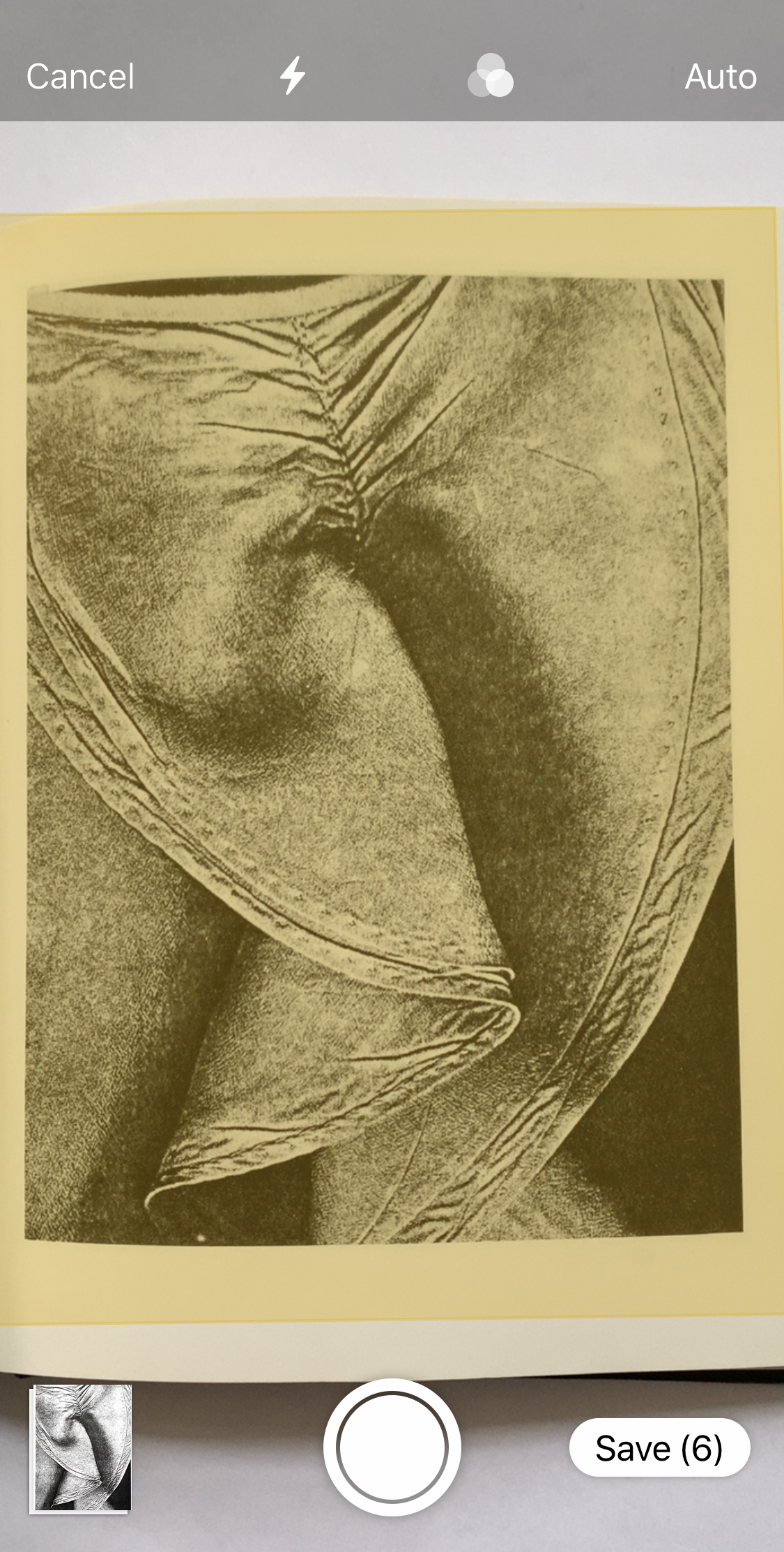

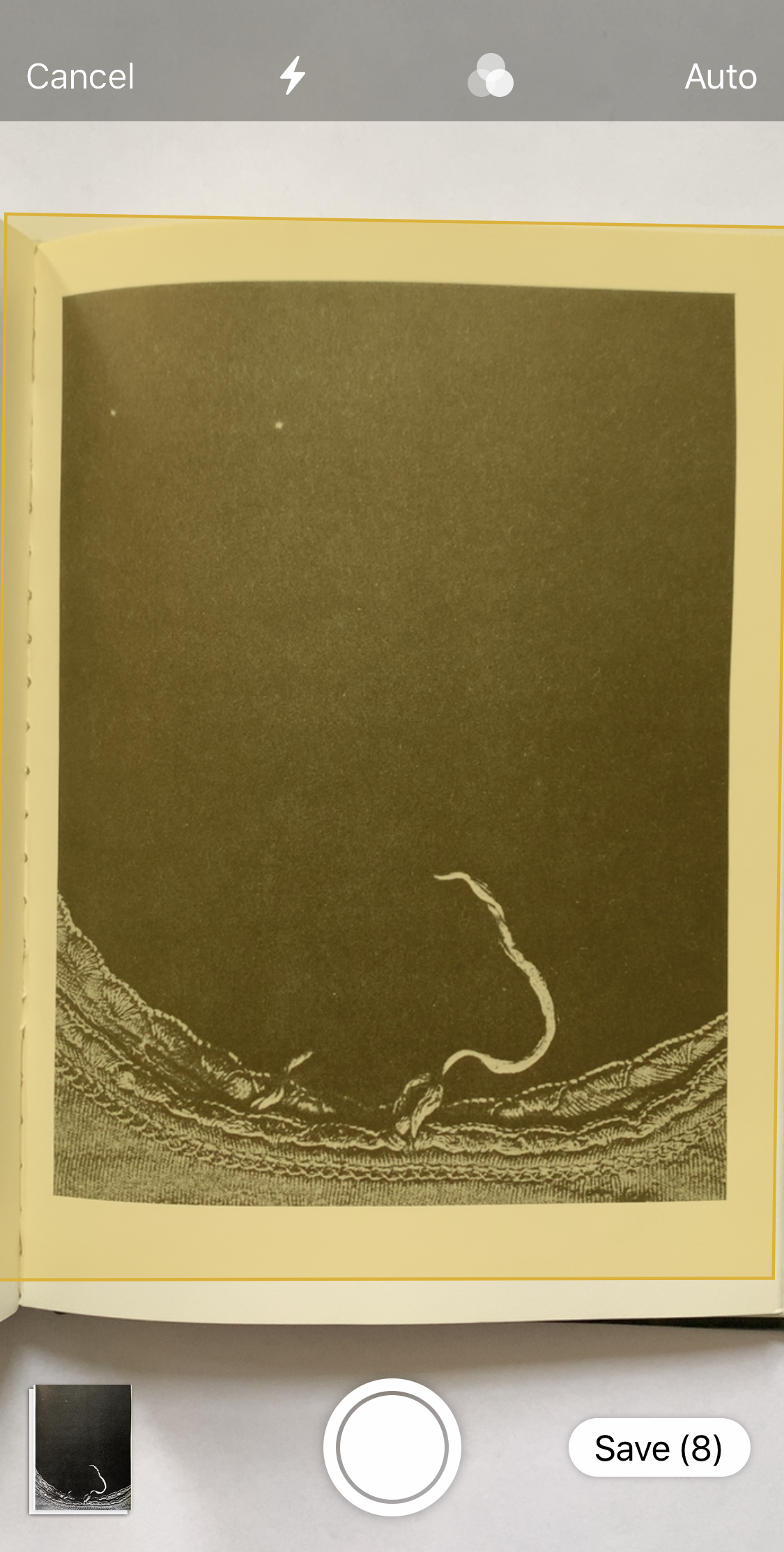

Hill wrote of domestic labor and confinement in her work. She wrote three books in her life, one was published through Kornblee Gallery. In 1962 she quit writing to favor housekeeping as a job but she kept a journal. She then began collecting objects too. She'd keep them in a hamper until the pile was big enough for her to go through them. She'd take them to a copy shop, copy the ones she found interesting and throw them all away, keeping the copies. In 1976, Kornblee exhibited Hill's Garments—a series of photocopies of lace, seams, buttonholes and zippers. Hill wrote that she had trouble finishing the exhibition because people started asking "questions like, Does the copier do pressing, too?" Six excerpts of this show were printed by New Letters accompanied by Hill's writing.

The website this text is found in is a reproduction of this piece titled Six Photocopied Garments. I plan to read the poetry that goes with the images at an online event or a series of online events. I've timed the website scrolling so I can read the words while the corresponding photocopy is on the screen. One can read the poems in their own time by inspecting the code of the website. I reproduce Pati Hill's work to attempt a discussion on gender based roles, domesticity and labor. There is an image of a fur coat reproduced here and I don't like it although I find the writing charming.

In Letters to Jill, Hill writes about publishing a lot and I really connected with this. She says "publishing a book on your own may be the cheapest and most efficient way in the end." She then goes on to write my favorite line: "Of course, there is still the question of distribution, but books have a life of their own. Some books move, even if you leave them on your back stairs in the boxes they came from the printer's in." This has never happened to me but I like how hopeful it sounds.